THE ELUSIVE STAR OF MEXICO

THE ELUSIVE STAR OF MEXICO

by Kenneth C. Landon (1985)

Located near a small Mexican village, high above the coconut palms and sugar cane fields of Central Mexico and far removed from the hectic bustling lifestyle of Mexico City, lies a lake whose peaceful, jewel-like serenity is crowned with towering festoons of starry white, solitary flowers. This Shangri-la-like description is not fantasy but is indeed fact. The following account recalls a memorable journey, including the search for and experiences with a wild and regal waterlily.

Perhaps a personal explanation and a bit of waterlily history, which set me on course for this native waterlily, would be in order. During the mid-1970’s I was fortunate to be in charge of an extensive private collection of native and hybrid Nymphaea (waterlilies) that had been collected and grown for botanical research and study. Over the years many professional and amateur water garden enthusiasts visited the collection, enjoying the waterlilies’ beauty. While many visitors were fascinated by the magnificence of Victoria and Euryale, there seemed to be a permanent congregation around a planting of so-called star lilies. Their tall stems pushed high above the water’s surface, terminating in the familiar star-shaped flowers of red, pink, violet, and purple.

The star lilies, as they are known in the trade and by most waterlily fanciers, have been around for some time. As water gardening became increasingly popular at the turn of the century, newly acquired Nymphaea from far off places held a mystique for collectors, and efforts to acquire them became intense.

Soon plant growers and breeders experimented with various native species, and numerous hybrids evolved. In 1892 a hybrid was produced by Benjamin Grey of Malden, Massachusetts, when an African species was crossed with a Mexican species, resulting in the first star lily. This unique plant, with its tall-stemmed, pale blue flowers, prompted other hybridizers to follow suit, resulting in new color additions to the star lily group. These new arrivals on the early water gardening scene were most welcome. Then, as now, they rank as some of the finest hybrids ever produced. The first star lilies were produced by crossing the African variety Nymphaea capensis var. zanzabariensis and its forms azurea and rosea, with the white-flowered Mexican species Nymphaea flavo-virens , sometimes referred to as Nymphaea gracilis. The resulting hybrids are intermediate between the two species with plant characteristics which tend to follow those of Nymphaea flavo-virens and floral colors and some leaf variations being supplied by Nymphaea capensis var. zanzibariensis.

The Nymphaea collection grew as new arrivals found their places under the hot Texas summer sun. Nymphaea capensis var. zanzabariensis was received from Pretoria in 1974. The new plants settled into the rhythm of sending up new flowers every third day. I noticed the marked difference between these parent plants and their offspring, the star lilies. The other parent, Nymphaea flavo-virens, was not included in the collection. Increased correspondence with prominent waterlily breeders and collectors indicated that this species had been lost from cultivation in the United States for years. Ironically, its eventual demise was brought about partly by the very hybrids it produced. To make things worse, it was the contention of several noted botanists that Nymphaea flavo-virens was extinct in Mexico too. This scarcity seemed to be explained by its initial rarity, which was compounded by the rigors of an encroaching population. If this is true, I thought, how unfortunate that such a beautiful species, with its rich heritage and botanical significance, could meet such a fate. At this point I decided to find out for myself what the real situation was with Nymphaea flavo-virens. Fortunately I had at my disposal much-needed archival information at the University of Texas at Austin, in addition to herbarium specimens and botanical field reports. Information on Nymphaea flavo-virens was scarce at best. There are at least seven white-flowered waterlilies (and a myriad of other white-flowered and closely related aquatic plants) indigenous to ‘Mexico. There are also some discrepancies regarding botanical nomenclature, further compounding the problem.

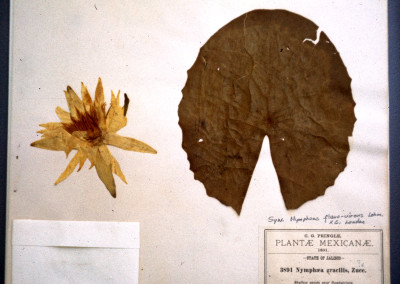

Despite these difficulties, I found a copy of an article by C. G. Pringle, who is credited with introducing Nymphaea flavo-virens to the United States in the early 1890s. Mr. Pringle, a traveler and plant enthusiast, also collected what he referred to as Nymphaea gracilis from an artificial pond near the station of El Castillo, near Guadalajara, Mexico. His original 1891 herbarium plates are on file at the University of Texas at Austin.

With such invaluable information, one would think that retrieval of new plants would be.a certain and simple enough task, but I found this was not the case. Current maps do not indicate the station of El Castillo, and to find an 85-year-old artificial pond near a place that apparently no longer exists leaves plenty of doubt even in the mind of the most ardent optimist. Worse yet, past experience has taught many a plant collector, especially this one, that under the best of circumstances wild waterlilies are not necessarily permanent residents of any given locale.

Herbarium specimens indicated another species, Nymphaea ampla, to be present in the area. This plant is the predominant day-blooming waterlily in Mexico, and its range includes practically the whole country, extending south throughout the remainder of

Central America. This species is closely related to Nymphaea flavo-virens , but is definitely a different species. If it were intermingled with Nymphaea flavo-virens, the likelihood of finding a pure strain of either species could be remote, if not impossible. With this information raising more doubt than promise, I decided to pursue a different course.

Mr. Pringle mentioned the Lerma River in his writings, describing it as the river that forms Lake Chapala, 31 miles south of Guadalajara. My next plan was to trace this river to its source and possibly to work somewhere short of Guadalajara. I secured detailed maps of the area and traced the river to its origin. I was surprised to find that the Lerma River is about 300 miles long. Its headwaters are formed by the melting snow of “Nevada de Toluca,” a snow-capped 15,000-foot peak 25-30 miles southwest of the town of Toluca. The Lerma then meanders west-northwest, towards the Pacific Ocean. The town of Toluca is approximately 40 miles west of Mexico City; the village of Lerma, 30 miles out of Mexico City, is where the newly-formed river intersects the highway. I decided to begin my search at this point.

I timed my trip to coincide with the seasonal growing habits of tropical waterlilies. Maps and notes in hand, and with my parents and my brother as companions, I hired a taxi one morning, and we were soon whizzing down the highway at remarkable speeds. We rolled into the village of Lerma at about 10 a.m. My spanish weak, I somehow told the driver we were in search of the river. It turned out that the river was just a bit further up the highway, and in practically no time we were there.

I got out of the car and surveyed the area. The river at this point was little more than a trickle. I noticed a side road further up the highway and motioned to the driver to take it. With a puzzled look, he took my advice, and we were soon bouncing down a dirt road that I hoped would lead somewhere. I tried to follow the river channel, which was anything but parallel to the road, but soon lost it. We went on for a mile or so as the road declined into little more than a donkey trail. It finally split, and we took the better road of the two forks. Our little yellow taxi must have been the big event of the day to the villagers, as most looked in amazement as we passed by. By now we were some distance from the highway and I had the feeling that everyone, except for myself and possibly the driver, was a bit tense. I must admit that things did not look very promising at this point, but the road took a turn towards the river, so I motioned to go on a little further. The terrain was hilly, making it difficult to see any great distance. The driver raced his engine to climb what must have been the largest hill so far. The taxi struggled along, finally approaching the summit. As the hilltop that was obscuring our forward vision vanished beneath us, I was overwhelmed by a seemingly infinite expanse of glistening water.

It was as if a lake had appeared out of thin air. From this vantage point I scrutinized the surface with binoculars for signs of waterlilies, but I couldn’t see any. The road continued down the hill, to where villagers were living right on the edge of the lake. I began a vain attempt at asking some of the villagers if they were familiar with “lirio de ague.” Their answer: a unanimous “no.”

Discouraged, I looked for the taxi driver, who wasn’t to be seen. He soon reappeared, coming up the road with a young local man. We asked the man a few questions, but got few positive answers. The man then asked if I would like to go on his boat, out into the lake. I did not see any boats anywhere, but I agreed. We curiously followed our new guide to a plant-infested slough. He picked up a long pole that was lying on the bank and slapped the water’s surface. This seemed odd, and I wondered if it had some ritualistic significance or if he was just trying to impress us. We stood on the bank and watched as he waded into the water up to his thighs. Bending over, he seemed to be reaching for something beneath the water. I was amazed to see him raise the end of a submerged boat.

The boat was about 20 feet long, made from what appeared to have been a solid log. Wrestling with the boat, he moved it towards the bank. He further lifted his end to discharge the water inside. As he tilted the boat, a multitude of fish, frogs, crayfish, snakes, and heaven knows what else poured over the side. These creatures flipped, jumped, and slithered in all directions, creating plenty of excitement for those of us on the bank.

Excitement subsiding, the newly resurrected boat sat high in the water. Its owner motioned to me, and while he steadied his end of the boat, I took up my position on the boat’s bow. There was room for another; my mother was, surprisingly, the only volunteer. The boatman picked up his long pole, and, standing on the stern, pushed us off.

Although we were in a lagoon, the boatman navigated us through recognizable waterways. A quagmire of aquatic weeds, both floating and submerged on either side of the channels, all but prevented any progress otherwise. The bow plowed through this floating garden, disturbing snakes that silently slipped into the depths around us. The whole area was a panorama of green. I noticed that even the corn on the bank grew up to the water’s edge, seeming to require little or no visible soil.

As we moved further from the shore, the floating green carpet finally yielded to open water. Navigation in any forward direction was now possible, and our guide quickly took a course toward what appeared to be the lagoon’s center. As he pushed the pole with long strokes, we glided over the mirror-like surface, our wake the only disturbance of an otherwise tranquil setting. As I looked back, our point of origin was now out of sight. Committed to the distance ahead, I donned the binoculars, finally focusing on something green and floating. It was too distant to identify, so I pointed in the direction and our guide gladly obliged. My curiosity was soon satisfied as we came upon great expanses of water snowflakes (Nymphoides peltatum). The deep green waterlily-like leaves, with their profusion of yellow flowers, were strikingly beautiful. Impressed but dismayed, we sat motionless in the midst of these living islands while I again scanned the water’s surface.

I perceived that we were near the center of the lagoon, as the banks were vaguely visible in all directions. No waterlilies were in sight, but to the west I noticed what seemed to be a misty haze. I almost dismissed it as a mirage, but thought it peculiar that it didn’t shimmer. I figured that we might just as well investigate it, so I pointed the way and we were again on the move. As we came closer, the haze solidified into a ribbon of white. The sun was now becoming a vision factor, making it difficult to see much of anything. With the glare in my eyes, I again focused the binoculars on what appeared to be some sort of white flowers growing on the distant bank. The color reminded me of something I had seen back at the village, wild asters blooming between rows of corn, like indigenous weeds; could this be what I was now observing? With our boat closing fast, it was soon apparent that the mysterious ribbon of white was not at all on the bank, but in front of it. My aster theory evaporated into renewed anxiety. The bank was still far in the distance, but the white ribbon dilated into a wispy layer above the water. It was becoming obvious that we were about to encounter something big. My first thoughts were of Nymphaea ampla, and its abundance throughout Mexico. I hopefully ruled this out, however, as the white haze was too far above the water’s surface.

My eager anticipation was aggravated by the sun’s intense glare, now rendering the binoculars useless. I felt like jumping overboard in an attempt to out swim the boat, but held my patience and kept still. Drawing closer, I became completely blinded by the water’s reflected glare, temporarily losing my fix on what had appeared to be the nearest plants. I knew they must be close by, so I turned to the guide and motioned to slow down. His pushpole dragging in the mud instead brought us to an abrupt halt. As I turned forward, at the bow’s edge stood three pristine flowers of Nymphaea flavo-virens.

Stunned, I stared at them, speechless and completely overwhelmed by the-dazzling white blossoms that seemed to radiate a countenance of their own. Regaining my senses, I photographed these first flowers and confirmed to my mother that we had realized success. She in turn informed the guide, in her workable spanish; he smiled and said, “Ah, flore del agua.” Photos and camera secured, I motioned to advance. Soon, as if by magic, we were engulfed in a fairyland sea of perpetual white. Sitting in the midst of this three-dimensional scene of blue sky and deep green leaves beneath a canopy of white, offered reward far in excess of any effort expended.

The retrieval of specimens was the next order of business, and I wasted no time in getting to work. The waterlilies grew in colonies, sometimes overlapping each other, but usually with distinct and separate plants. The previous season’s germinating tubers formed groups of from four to eight adult plants, intermingled with a few juveniles. A stand of from four to six flowers marked the center of isolated colonies, which averaged five feet in diameter. In such growing conditions the flowers averaged four inches across, rising one foot, more or less, above the water’s surface. The pure green leaves, crowded and overlapping, also averaged about four inches in diameter. The water was approximately two feet deep, offering easy recovery. I assumed a prone position on the bow of the boat, my arms extending into the water, feeling for plant crowns. I proceeded to dig my fingers into the rich black mud. Suddenly I felt something move past my arms, but dismissed it as a harmless fish. Our previous encounter with snakes was vivid enough in my mind, but that just didn’t seem important now. Even if the world’s largest and meanest snake had appeared on the scene, it wouldn’t have mattered, as I had hit pay dirt and was not about to be deterred. I quickly secured a handful of tubers and two adult plants for herbarium specimens. Making sure the tubers were sound, I washed the mud from my hands and gave the signal to head for home. As our boat picked up speed, I reached in my pocket for a plastic bag. The plants and tubers now put away, I turned westward. Already the waterlilies seemed far removed, and, as the white flowers faded in the distance, I silently bade them farewell. The ride to shore was made more enjoyable by a relaxed sense of accomplishment. We were greeted at the shore by my brother and stepfather. They, in turn, were joined by an entourage of curious villagers. The shore party approaching, my brother and stepfather, in unison, asked if I had found anything. I replied by raising the plastic bag, smiling, as they looked at each other in astonishment.

My mother and I disembarked, as our guide steadied the boat. He then jumped overboard, tilted the craft on its side, and again sank it into silence. Swatting off a leech or two, he then rejoined us.

The taxi driver, while stowing our cargo, asked our guide why the boat was kept underwater. He had two reasons. First, he did so to eliminate cracking due to drying out, and second, it reduced the possibility of any unauthorized excursions by adventurous children. After I paid the guide, I prompted the driver to ask a few more questions. I found the name of the lake to be “Laguna Lerma.” I was also surprised to learn that during the winter months the lagoon often froze over. This, while unexpected, was understandable, as the altitude was over 6,000 feet. Such a climate was evidenced by the absence of permanent tropical vegetation, such as banana and palm trees.

Questions concluded, our guide asked if I would take some pictures of him and his family. I gladly obliged, and the taxi driver wrote down his mailing address for me so that I could return the pictures. Shaking his hand, I again thanked him for his efforts and boarded the taxi. I felt lucky when we found our way back to the highway. With its smooth surface beneath us, we headed for Mexico City.

The addition of Nymphaea flavor-virens to the collection was a welcome event, and since its recovery in 1976, it has been grown yearly. Horticulturally speaking, it is an easy species to grow, and it blooms and fruits throughout the summer. When ample soil and nutrients are restricted, it quickly calls it a season and goes into dormancy. Last year, I included Nymphaea flavo-virens in a planting with its star lily counterparts. It was, perhaps, not the queen of the pool, the white flowers somewhat dwarfed by those of its multi-colored hybrid children; but it was superb. As I singled out one of the pure white flowers, I was reminded of a place far to the south. A place where the same white flowers adorn the shimmering waters of a little-known lagoon. A place where the elusive star of Mexico reigns supreme.

* * *

Recent comparative evidence shows Nymphaea flavo-virens to be quire rare, despite reported sightings in south Central America, Brazil, and Peru. Its primary geographical distribution is concentrated in, but not confined to, central Mexico. Isolated colonies, like that of Laguna Lerma, may be encountered elsewhere along or near the Lerma River as it advances westward. As previously theorized, when areas of Nymphaea flavo-virens and Nymphaea ampla overlap, natural hybrids evolve. These intermediates may have possibly contributed to early confusion regarding correct botanical nomenclature.

In any case, the species name Nymphaea flavo-virens Lehm., following the description of J.G.C. Lehmann (1852) and corroborated by H.S. Conard (1905) in his monograph The Waterlilies, has been used up to the present. The other name of Nymphaea gracilis Zuccarini (1832), with which it had been primarily confused, then thought to be a Nymphaea ampla variety, was discarded by Conard. Dr. Conard, uncertain, apparently based his decision on descriptions and somewhat confusing herbarium material. However, studies in Mexico and the United States have recently rendered convincing evidence indicating the synonymity of Nymphaea flavo-virens Lehm. and Nymphaea flavo-virens Zucc. If this is true, then Nymphaea flavo-virens Zucc. should be the correct botanical name of this species by rule of precedence.